A little while ago LET'S ANIME explored the Japanese cartoon fanzine culture of the 1980s, a self-published world of anime show synopses and iffy translations illustrated with anime fan artwork ranging from bad to beautiful. Now let's move the clock forward a bit and take a look at what was happening to anime zines in the decade of grunge, Clinton, clear beverages and America Online - the 1990s! Zine culture was America's underground - a fiercely independent self-published universe of crude comics, biased journalism, conspiracy theories, and reviews of whatever record labels would send you that you could later sell for beer money. Distributed by an ad hoc network of comic shops, telephone poles, record stores, and your hipper bookstores; held together by comprehensive review journals like Factsheet Five; the world of zines was embraced by the pop culture tastemakers and became as emblematic of "Generation X" as a copy of Nirvana's "Nevermind" or one of those tribal tattoos that white people once felt they could get away with. And much like Mudhoney or free zines for prisoners, Japanese cartoon zines were a part of that world.

For many anime zines, the early 1990s were merely a flashier version of the 1980s. Fan fiction in particular had yet to make the digital transition and fanfic was still being published in giant plastic-comb bound volumes like the "Anime House Presents" shown here, featuring a lovely Char Aznable cover and stories about Mospeada, Lupin III, Saint Seiya, Dirty Pair, Catseye, and a recurring comic strip mashup between Voltron and Bloom County. Meanwhile in the Yamato world, Star Blazers fans were presenting their Star Blazers/Yamato fan tales in APAs like this one, named after the queen of Iscandar because all Yamato zines were named after female characters. They just were, okay?

But new and strange forces were looming, Godzilla-like, over the horizon. The "desktop publishing revolution" meant that graphic design and typography were no longer the private reserve of print shops and linotype operators. Suddenly regular folks with a couple thousand bucks to blow on computers and printers could create professional-looking documents at a fraction of the cost of traditional methods. The new wave of computer-aided fanzine design, combined with the falling prices of high-quality photocopier equipment and the seemingly unstoppable march of Kinko's across the land, meant anime zines could be made better, faster, and stronger than ever before.

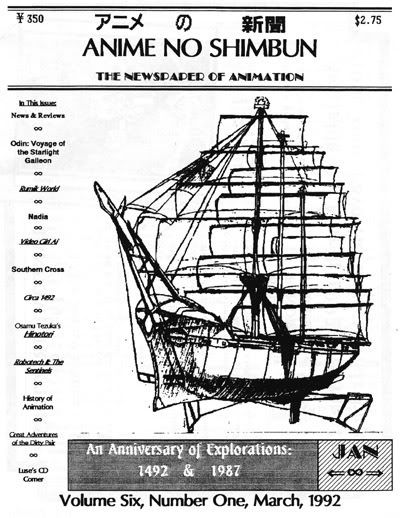

One early computer-aided zine was Anime No Shimbun, the offical publication of the Japanese Animation Network, a former EDC chapter in Richmond VA headed by the late Roy Bruce. Anime No Shimbun featured synopses of current and not-so-current titles such as Odin, Nadia, and early moe fave Video Girl Ai, along with reprints of Baycon synopses and reviews of the Robotech II: The Sentinels comic by local favorites John and Jason Waltrip. Fan fiction, Japanese cultural information, general animation news, and a fan comic story entitled "Urusei Gakira" written and drawn by future perennial anime-con guest Steve Bennett helped to fill the zine's pages.

The East Coast was definitely representin' as we see from another 1992 zine, Atlantia, which is the offical news bulletin of the Atlantic Anime Alliance. What is it with fan clubs publishing "official" newsletters? Was somebody out there printing unofficial newsletters? Judging from the editorial in this issue the AAA seemed to be made up of New Jersey area fans determined to become the focal point of anime fandom on the east coast. Let me know how that's working out, guys. A big 3X3 Eyes article by the late Steve Pearl, an article about the AnimEigo Bubblegum Crisis releases and a synopsis of Ranma 1/2 "Get Back The Brides" rounds out the issue.

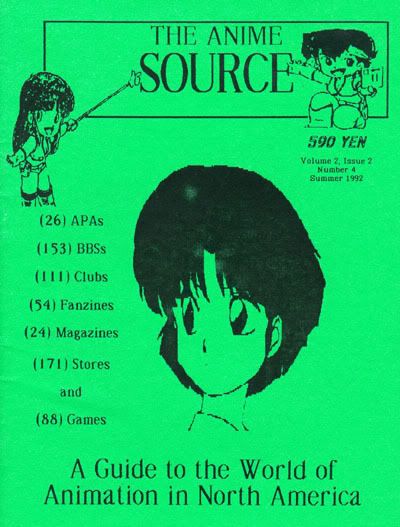

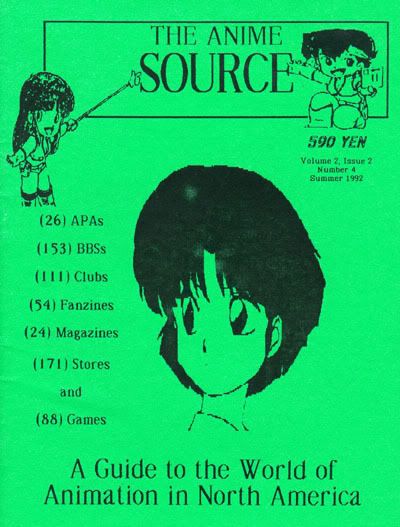

If we're talking about trying to get anime fans to come together in peace love and understanding, for my money the must-have zine of 1992 was The Anime Source. Like the cover says, it lists contact information for 26 APAs, 153 computer BBSes, 111 (count' em!) anime clubs, 54 fanzines, 24 magazines, 171 stores, and 88 games. If you couldn't get your anime freak on with this zine then there is simply no hope for you. Publisher Alec Orrock also was behind the zine From Side To S.I.D.E., a entertaining magazine with a focus on Orange Road, Gundam, Yawara, and a fan translation of the wacky crossdressing idol singer manga "Twinkle Idol Stars".

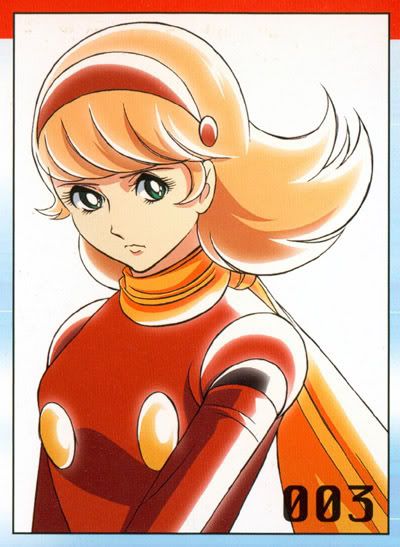

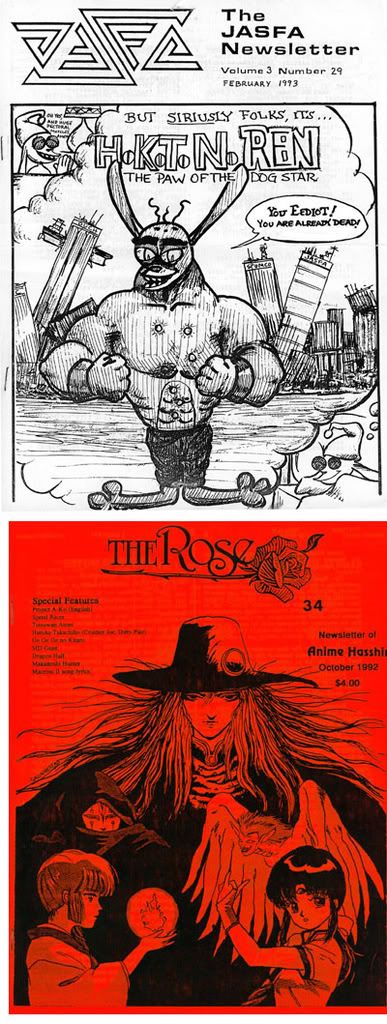

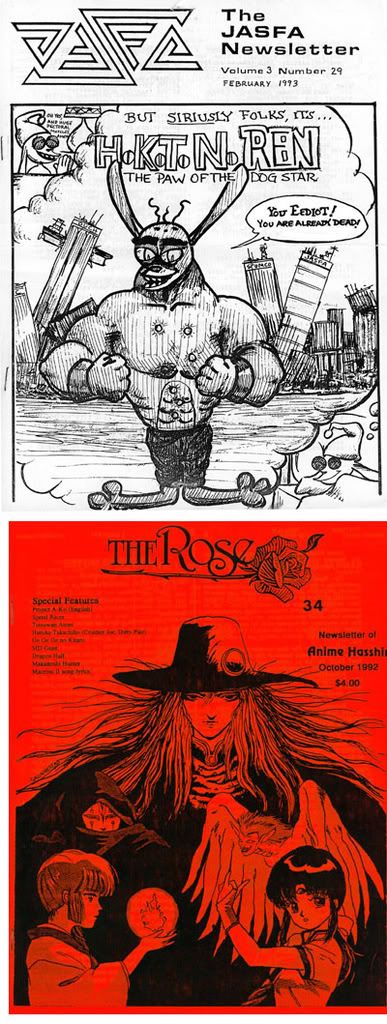

Meanwhile back on the East Coast the Baltimore anime club JASFA was continuing to crank out their newsletter, a short and snappy monthly that cut through the nonsense and let you know what the club was watching and when. Translated episode titles make back issues of this zine priceless, unless you already knew that episode #46 of Saver Kids was titled "The Earth Breaks Up In Five Minutes!!" This issue not only has a great Ren & Stimpy cover - yeah, you KNOW it's the '90s when they start hauling out the Ren & Stimpy references!!- but also features a mention of some new show called "Sailor Moon". I wonder if that will be popular. Another 80s survivor was The Rose, the newsletter of Anime Hasshin, which continued to provide news and information to readers around the country. Always tons of reviews and fan art in the Rose, and this issue was no exception with articles about Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro, Speed Racer, Haruka Takachiho and his Dirty Pair, Dragon Half, and fanart by, among others, Robert "Slow Bob" DeJesus.

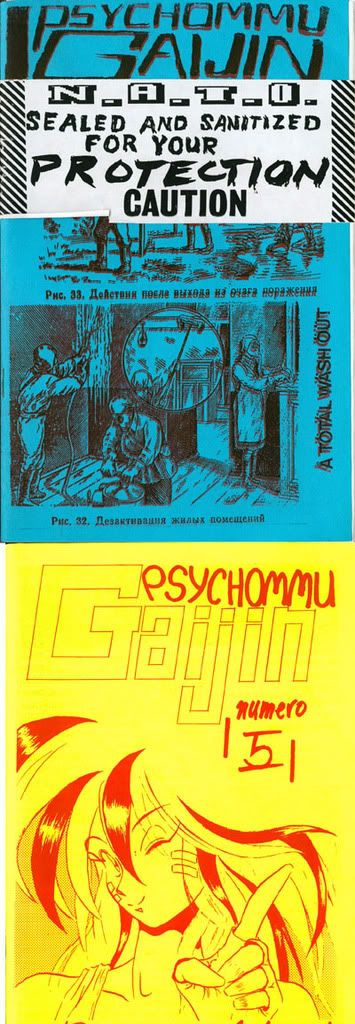

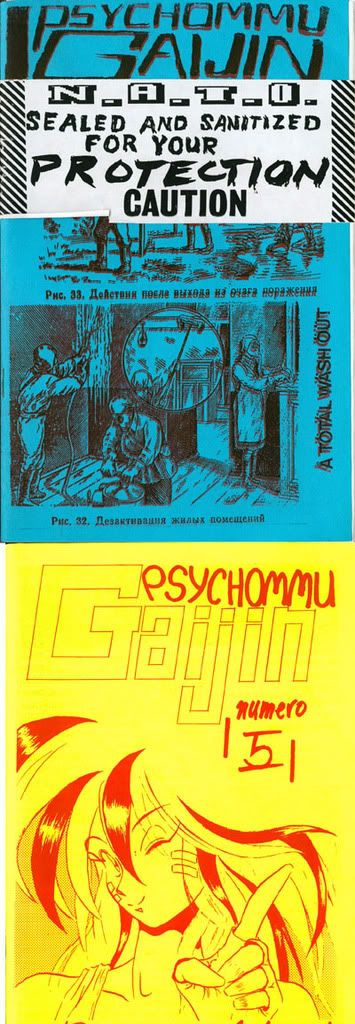

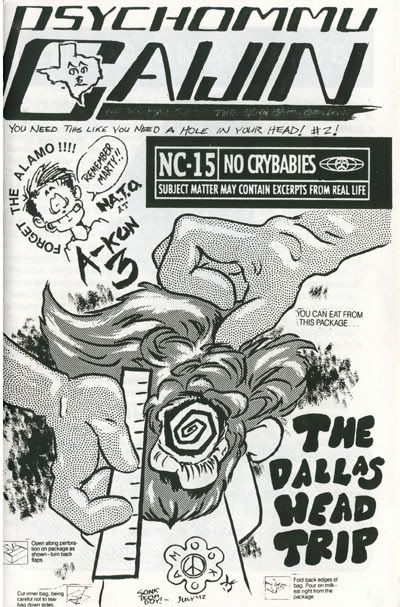

And if we rumble way up north for a change of scenery, we might come under guitar-playin' natural distaster attack from the National Anime Terrorist Organization of Minneapolis MN and their zine, Psychommu Gaijin! Pgaijin, as it came to be known, was the low rent punk rock cut and paste fuck you antidote to the rest of the anime fanzine world, much of which could be politely described as, shall we say, slightly anal-retentive. Not Psychommu - spearheaded by young clubbing indy-rock insomniacs, burnt-out fandom gurus, and trouble-making beer enthusiast anarchists, the PGZine cheerfully mixed medical illustrations, band flyers, Kennedy assassination cartoons, Votoms drinking games, a anime version of Battlestar Galactica and weed-huffing Ninja High School parodies with reviews of Macross videogames and con reports. Psychommu Gaijin transmogrified into a website, a

Yahoogroups mailing list, and a blog, yet continues to appear sporadically as a free zine handed out at various anime conventions, to the obvious dismay of the authorities.

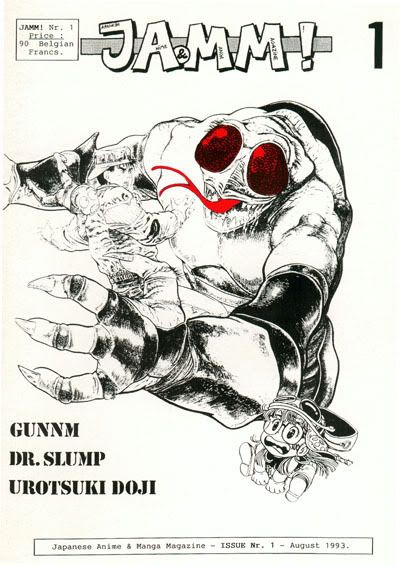

Across the pond in Belgium the euroanime fans were doing it for themselves with the handsome, glossy-covered, English-language (thanks!) Japanese Anime & Manga Magazine or J.A.M.M. for short. Yes, even in Europe fans felt the need to name themselves with awkward acronyms. The sophisticated European zine culture thought nothing of producing long, detailed essays on Urotsukidoji and ero-anime in general, complete with illustrations (!). Of course there's also some Dr. Slump to take the edge off.

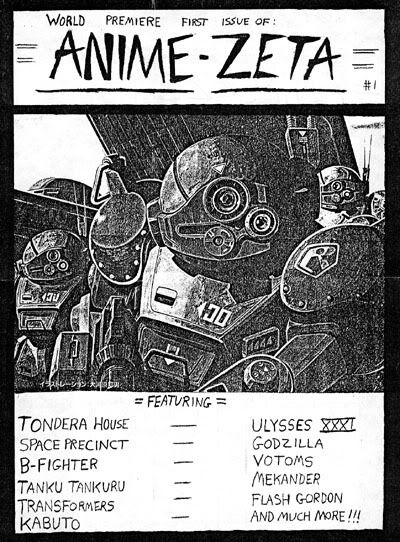

From Florida came the first and perhaps only issue of Anime Zeta, probably the only anime zine to (a) review the Bible cartoon Flying House, and (b) review the Bible cartoon Flying House without once mentioning its religious content. Magazine and newspaper clippings, typewritten articles about Daltanias next to handwritten captions, illustrations lifted wholesale from reference books, and a "news article" about Ted Turner - not Turner Broadcasting or Warner, just Ted Turner - getting the rights to Doreamon (?) make this one a real curiosity.

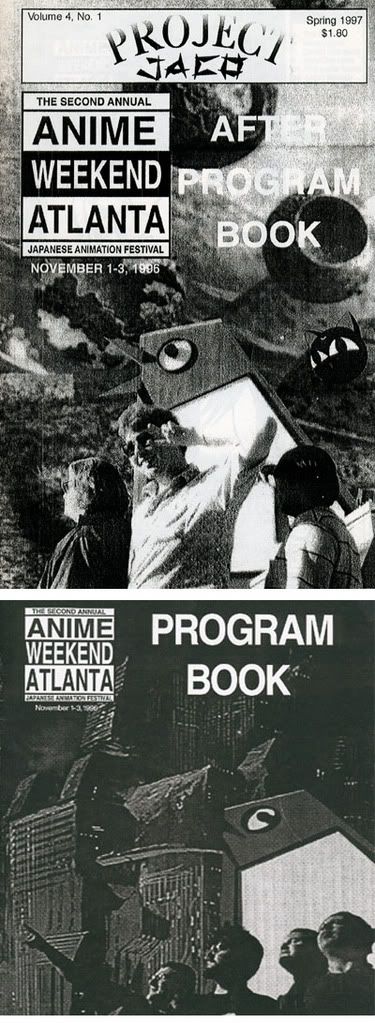

If there's one thing Florida had a lot of, it's anime clubs. Orlando itself was home to several different outfits, all fussin' and feudin' with each other to see who could be the fussinest and the feudinest. The Japanese Anime Club Of Orlando, a.k.a. JACO, was so impressed by their visit to AWA 2 that they produced a 52-page zine all about the trip. Seriously. Packing up the car, getting traffic tickets, stalking that girl who looks like your ex-fiance, that rocking air guitar performance of the end theme to Megazone 23, photographing their own version of the cover of the con's program book; it's one sloppy love letter of a zine. Not every issue of "Project JACO" was a mash note to AWA, though. Reviews of Bounty Dog, Chirality, and a photo essay of their trip to EPCOT Center rounded out the color-cover Summer 1997 issue. JACO

eventually started their own convention, Jacon, thus starting the process which enabled the rest of us to transition from saying "Florida has too many anime clubs" to saying "Florida has too many anime cons."

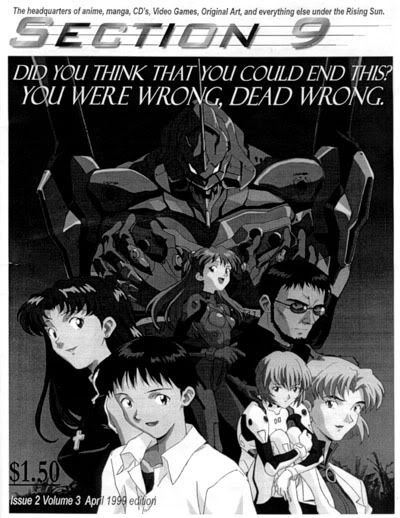

As the decade sped by in a blur of stonewashed jeans and lackluster techno remixes, anime zines got a lot slicker. Scanners got cheaper and processors got faster and screencaps became something more than just a lucky Polaroid of your TV screen. Section 9, produced by the Grand Rapids Area Anime Club, is representative of its era for several reasons: most of the reviews are for English-language professional releases of titles like Tenchi Muyou, Tekken, Evangelion, and Idol Hunter; the con reports have adopted the modern emphasis on photos of doofuses in costumes, and there is the first mention of some mysterious something called "DVD". Whatever could THAT be? Lots of links to those new-fangled 'web pages' keep this zine squarely in the fast lane of the 'information superhighway'.

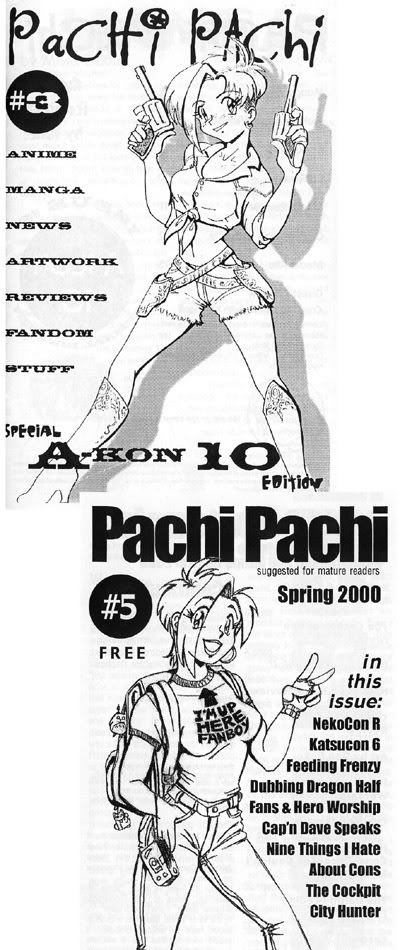

The 90s wound down claiming print media was dead and soon we'd all be dot-com millionaires living in a virtual reality world having groceries delivered by Kozmo.com. Zine culture faltered as Jim Goad did jail time, Factsheet Five collapsed under its own weight, and everybody else got jobs working for "Sassy." Anime fan culture transitioned from a club-based fandom to becoming a migrating herd travelling from one hotel ballroom to another. Anime zinesters manned fan tables hawking their anime zines to anime convention crowds who'd rather spend their cash on actual licensed merchandise rather than some homemade pamphlet. Print zines moved towards a "free" model, as exemplified by "Pachi Pachi".

Edited by the mysterious "JobsTurkey", Pachi Pachi was distributed free at whichever conventions the editor found him-or-herself attending. How-to articles on cosplay and anime music videos kept this zine topical and reviews of anime, manga, CDs, etc. were short and to the point. Later issues focused on the anime fan culture itself, which by 1999 had assumed many of its current signifiers - squealing girls, obsession with voice actors, cosplay worship, and general fan entitlement ego-hatting. And in spite of all the editorializing anime zines could muster, the situation hasn't changed much.

Ten years later anime fandom expresses itself online through blogs, through columns on websites large and small, and through a million message boards and livejournals. No longer do we have to sneak copies from the student center office or get a job in the print industry to support the toner monkey on our back. Some of us pine for the good old days of making our marks upon the world with gluestick and X-Acto, but at the same time, nobody misses clearing paper jams or shelling out for PO boxes. We here at Let's Anime look forward to the media-cube digi-zappers of 2029 reminiscing fondly about those quaint, childish "anime blogs" of yesteryear.

(all artwork and text (c) the original creators. Thanks to you, the zine publishers of the 1990s!)